We picked up our girls from Columbus on Friday. They’ve been with my mom having summer fun for two weeks. On Saturday, we took a detour home through Eufaula. Saturday’s drive home wasn’t just a route—it was a memory unfolding mile by mile. After lunch with Jennifer’s family in Eufaula, we chose Highway 431 instead of the usual path to Ringgold. That stretch from Seale to Anniston, winding through rural Alabama towns like Seale, Crawford, Opelika, Lafayette, Roanoke, Munford, and Centre, felt like traveling through time. In Centre, near Lake Weiss, we turned back towards north Georgia.

We even detoured near Anniston to show my daughters Camp Mac—a place that once held my summers as a camper and later as a counselor. Though the camp was prepping for its final 10-Day Term of the summer, and we didn’t stop officially, the roads and signage whispered old stories. My nephew James, now a counselor himself, carries that legacy forward.

But what stirred my heart most on that drive was passing through Russell County—especially near Seale and Crawford, where my grandparents’ farm stood just off Highway 169. Growing up, that stretch of land was my second home. And my grandfather, a farmer and county commissioner for 24 years, was my compass.

He taught me how to drive—starting on dirt roads at age nine. And even after I earned my license, he still corrected my driving with steady commentary from the front passenger seat. Not so much a backseat driver, but always present, always teaching.

On Sundays, we attended Seale United Methodist Church together. A congregation of 20 or 25 on a good day. Most Sundays, I was the only youth—or one of two or three. Yet it felt whole. Sacred in its simplicity.

He farmed cotton and soybeans when I was young—no animals by then, but plenty of work. I remember riding atop the cotton picker, delivering harvests to the cotton gin, and playing in the wagons filled to the brim—always reminded to stay alert so we wouldn’t smother under the weight. Later, when the crops ended, he planted pine trees for future harvest, thinking ahead, always rooted.

There were no electronics in our world back then, but it didn’t matter. We had fun: honest, muddy, imaginative fun. And once a year, he hosted county barbecues at the farm—whole pigs roasted and a family secret recipe for Brunswick stew served to the county workers. During election years, we might have a barbecue as a campaign event, humble and hearty. I can remember even helping him campaign outside the Crawford Volunteer Fire Station and Rainbow Foods (Grocery Store).

I became his driver, too. To the courthouse in Phenix City, to Montgomery, even up Highway 431 to Huntsville for a state county commissioners’ meeting. It was on that same route—now traveled with my wife and daughters—that memories stirred, quiet and bittersweet.

He was born March 9, 1928. I arrived fifty years and six days later. He passed in May 2004, just two months after Jennifer and I got married. He never got to meet our girls, which still aches. They won’t ride cotton wagons. They won’t sit beside him at the tiny church pew in Seale. They won’t hear his voice from the passenger seat reminding them when to brake.

But they carry him anyway. In my stories, in stories shared by my mom. In the routes I choose. In the grit and grace he taught me.

In Memory:

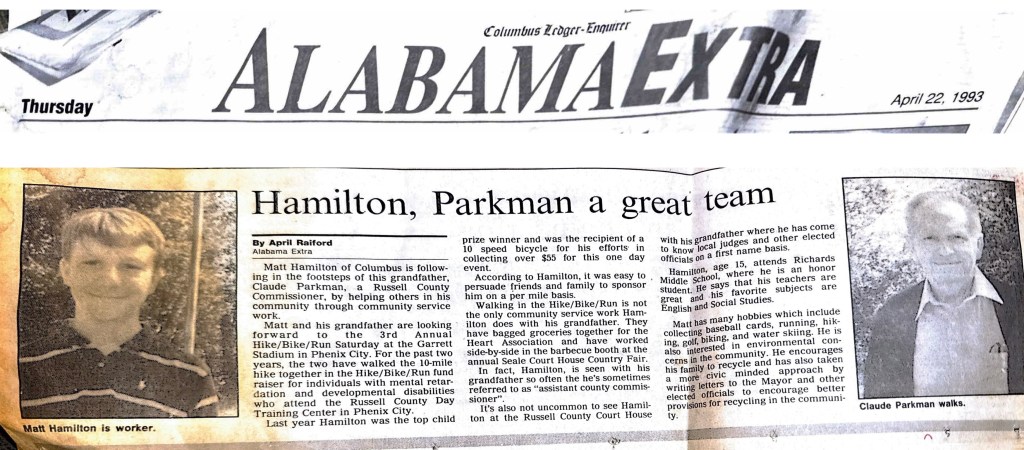

This story is dedicated to my grandfather, Claude Parkman, Russell County Commissioner from 1972 to 1996, farmer, mentor, and passenger-seat coach. He taught me how to drive, how to campaign, and how to listen to the land.

Though he never met his great-granddaughters, I carry him with me every time we pass through Seale, turn onto Highway 169, or find ourselves drifting down the same stretch of 431 we once rode together. His story lives on in the roads we travel, the work we do, and the family we build.

An article from April 1993 in the “Alabama Extra” section of the Columbus, GA newspaper.

Seale United Methodist Church. I took this picture in December, 2014.